The election of Kamala Harris as the first Black vice president and the first graduate of a historically Black college or university to hold the position has put the historical significance of HBCUs into focus. Harris’ victory is just the latest in a long political legacy of HBCUs. It is generally well-known that the more than 100 HBCUs in America have produced many of the most prominent Black leaders throughout the country’s history. But the full extent to which HBCUs have been involved in political activism and advancing Black freedom is often overlooked. From the Reconstruction era to the Civil Rights Movement to the current political landscape, HBCUs have been key to fighting for the rights of Black Americans.

Jim Crow era student activism

Growing from a handful of pre-Civil War schools dedicated to educating Black students, such as the African Institute (now Cheyney University) and Lincoln University, most HBCUs were created during or soon after Reconstruction to educate the newly freed Black population in the American South as well as Black Americans from throughout the country.

Protesting on-campus issues

By the 1920s, students at these institutions were starting to organize, even against their own schools’ administrations. When popular Florida A&M University (FAMU) president Nathan Young was fired in 1923 and replaced by a president who accommodated segregation, students spent the next year protesting, boycotting classes and allegedly setting fire to several campus buildings until the school changed leadership.

Two years later in 1925, Fisk University alum and NAACP co-founder W.E.B. Du Bois visited his alma mater, where his daughter was graduating. Familiar with complaints from Fisk students that the school’s conservative president Fayette McKenzie was creating an overly restrictive atmosphere and squelching opportunities, including rejecting an on-campus NAACP branch, Du Bois fiercely urged students and alumni to resist. This kicked off a raucous wave of protests and student strikes that succeeded in ousting McKenzie.

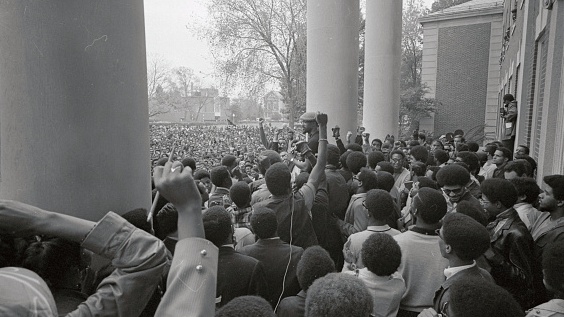

Additionally, Howard University has long had a particularly activism-oriented student body. In 1925, Howard students were inspired by Fisk’s student body to go on strike and force the school to eliminate mandatory ROTC participation for students.

Zoom filter makes lawyer look like cat during court hearing in viral video

No to Jim Crow

Branching out beyond on-campus issues in 1934, Howard students held two high-profile protests that year. Early in the year, students engaged in Washington, D.C.’s first anti-Jim Crow sit-in, protesting the segregated restaurants of the district in response to pleas from Representative Oscar De Priest, the only Black member of Congress at the time. In December 1934, Howard students wearing nooses around their necks picketed the U.S. Justice Department’s National Crime Conference, which was refusing to discuss lynching as a national priority.

The Southern Negro Youth Congress

HBCU activism reached an unprecedented scope in 1937. That year, students, drawn from nearly every Black college operating at the time, as well as representatives of groups like the YMCA, the Boy Scouts, the Girl Scouts as well as Communists, met at a conference in Richmond, Virginia, and formed the Southern Negro Youth Congress. The group, which had thousands of members at its height, engaged in labor organizing and voter rights education across the South. The SNYC also advocated for social issues such as improved healthcare in Black communities and the addition of African American history in public school curricula.

The SNYC was eventually overwhelmed by the opposition, as the organization was targeted by the anti-communist FBI, the Ku Klux Klan and segregationist police commissioner “Bull” Connor, who took over the police force in Birmingham, Alabama, where the SNYC was headquartered. By 1948, it had mostly ceased to function. But it did not go quietly. In 1946, the organization hosted more than 2000 delegates in an anti-Jim Crow conference held in Columbia, South Carolina. The event, featuring key appearances by Du Bois and Paul Robeson, was, according to a retrospective by the Carolina Panorama newspaper, “the largest human rights event the South had ever seen, with a class analysis of racism and a call for a black and white united front.”

Source: HBCUs Have Long Been At The Forefront Of Black Political Empowerment